This is part two of a report published by the Council on Foreign Relations. You can read part 1 here.

Where are the heroin and fentanyl coming from?

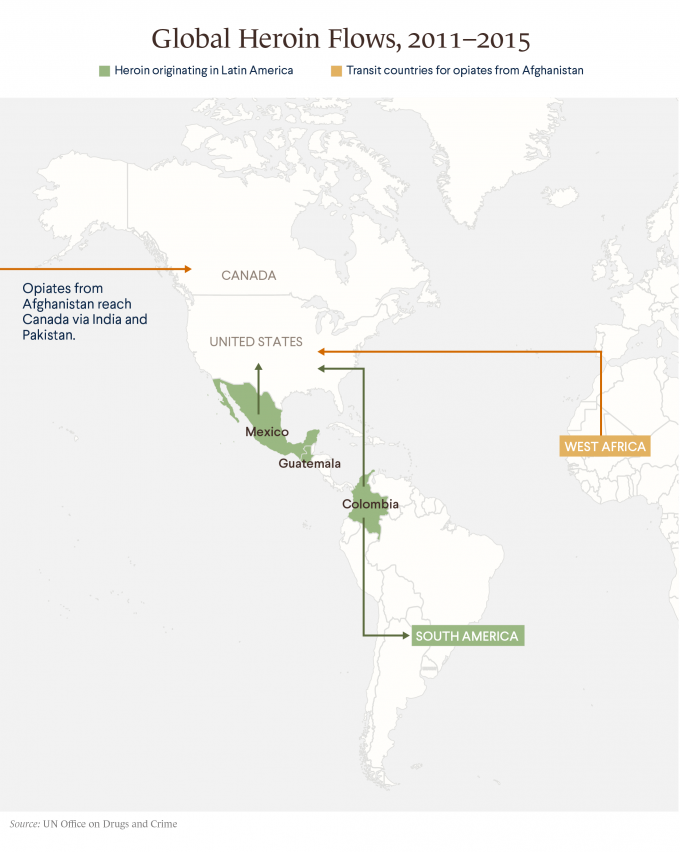

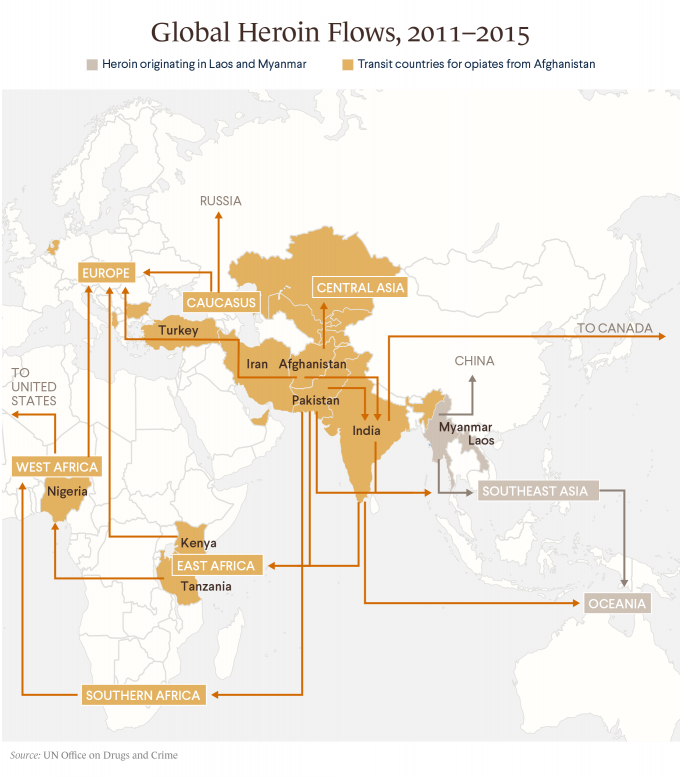

The opioid crisis has also become a national security concern. Most of the heroin coming into the United States is cultivated on poppy farms in Mexico, with eight cartels controlling production and operating distribution hubs in major U.S. cities. Mexican cartels, which the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has called the “greatest criminal drug threat to the United States,” typically smuggle narcotics across the U.S. southwest border in passenger vehicles or tractor trailers. Large quantities of heroin are also produced in South American countries, particularly Colombia, and trafficked to the United States by air and sea. Although most of the world’s heroin comes from Afghanistan, only a small portion of the U.S. supply is produced there.

Most fentanyl coming to the United States is produced in China, U.S. officials say, and commonly transited through Mexico. Chinese authorities “have struggled to adequately regulate thousands of chemical and pharmaceutical facilities operating legally and illegally in the country,” says a 2017 report issued by a congressionally mandated commission.

What has the United States done to restrict foreign narcotics?

Over the past decade, the United States has provided Mexico with nearly $3 billion in counternarcotics aid, including for police and judicial reforms, in a program known as the Merida Initiative. The initiative, which U.S. officials say led to the capture of some top cartel leaders, including Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, has continued under the administration of President Donald J. Trump, though funding has declined in recent years. Through a similar partnership with Colombia, the United States has provided almost $10 billion since 2000; it effectively drew to a close following the end to civil conflict there in 2016.

The DEA, the leading U.S. agency involved in counternarcotics, has also coordinated efforts with China, which has designated more than one hundred synthetic drugs as controlled substances. Beijing banned production of four fentanyl variations in 2017, although some analysts fear these moves will only spur clandestine labs to create new alternatives.

Recent U.S. administrations have also increased the number of border patrol agents to approximately twenty thousand. Heroin seizures and trafficking arrests more than doubled between 2010 and 2015, mostly near the southwestern border.

In his first weeks in office, President Trump issued executive orders directing the construction of a southern border wall and additional increases to the number of border patrol agents. Some analysts say a wall would do little to curb drug flows, however, as most illicit drugs are smuggled through ports of entry.

What are some efforts to restrict domestic supply?

Federal agencies, state governments, insurance providers, and physicians all influence the supply of opioid medications.

Federal regulators have introduced new limits on opioid prescriptions, reducing the total nationwide by 18 percent from their 2010 peak to 2015, according to the CDC. The agency issued guidelines in March 2016 advising physicians not to prescribe opioids as a first-line therapy. The DEA reduced production quotasfor pharmaceutical manufacturers by at least 25 percent that year for opioids categorized as Schedule II drugs, or ones that are currently accepted for medical use but carry high risk of misuse; these include oxycodone, fentanyl, and morphine. The agency has proposed additional cuts for 2018. Reporting by the Washington Post and 60 Minutes, however, found that a law passed in 2016after heavy lobbying by pharmaceutical companies has effectively stripped the DEA of its ability to freeze suspicious shipments of narcotics.

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced in August 2017 that the Justice Department will hire a dozen attorneys to investigate health-care providers suspected of dispensing prescription opioids for nonmedical use.

Additionally, lawmakers in more than fifteen states have passed or are considering legislation limiting opioid prescriptions since the start of 2016. States including Mississippi, Ohio, and Oklahoma, as well as dozens of cities, are suing pharmaceutical companies, alleging they overstated the benefits of prescription opioids and concealed the risks.

What is the United States doing to reduce demand?

Previous federal antidrug campaigns relied on incarceration to deter drug use and trafficking but have been widely criticized for failing to keep people from cycling in and out of prison and for disproportionately targeting African Americans. In recent years, federal and state officials have shifted toward prevention and treatment.

President Barack Obama reduced prison sentences for hundreds of nonviolent drug offenders during his tenure. However, he failed to secure legislation that would have eliminated mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug crimes. His administration also established hundreds of new drug courts, which proponents say are a more effective alternative to incarceration. Drug courts, the first of which was launched in 1989, under the George H.W. Bush administration, provide nonviolent offenders an alternative to the criminal-justice system that involves monitoring and rehabilitation services rather than prison time.

In recent years, federal and state officials have shifted toward prevention and treatment.

In 2016, President Obama signed legislation authorizing more than $1 billion in funding, largely in the form of state grants, to expand opioid treatment and prevention programs, as well as make the drug naloxone, which can counteract opioid overdoses in emergencies, more readily available.

Some city and local governments have launched what are known as harm-reduction programs, which focus on limiting virus transmission and overdoses through the promotion of safer drug use. Critics of such programs argue that decriminalization would lead to higher rates of drug use.

In October 2017, President Trump declared the epidemic a public health emergency, freeing up some federal grant funds for states to direct toward the crisis and loosening restrictions on access to treatment. Meanwhile, a presidential commission has recommended other policies to combat the crisis.

Many working on the issue believe the government should direct more resources toward educating the public about risks. “I don’t think we’ve done enough in terms of informing people about the dangers—about the nexus between opioid medication and heroin and illicit drugs,” says Brennan. “If we did the kind of information campaign that was so successful with tobacco, I think we could see terrific results.”

How are other countries dealing with opioid addiction?

The Netherlands. The Netherlands permits the sale and use of small amounts of cannabis to steer users away from so-called hard drugs, such as cocaine and heroin, and has implemented harm-reduction policies. In the 1990s the country began offering heroin at no cost, and the rate of high-risk or so-called problem use has halved from 2002 to some fourteen thousand in 2012, according to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Proponents of decriminalization point to the Netherlands for evidence that these policies work, though critics claim they have not curbed organized crime.

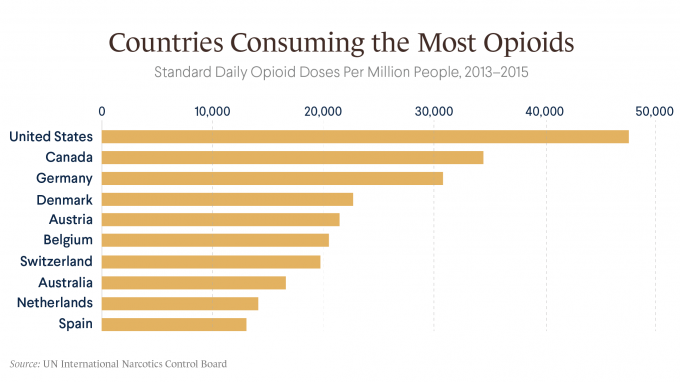

Canada. Amid a growing opioid crisis of its own, Canada has authorized the opening of supervised consumption sites and partnered with China to curb fentanyl flows into the country, but the health ministry says “huge gaps” remain in the government’s ability to track and respond to the problem. A government reporton opioid-related deaths in 2016—there were some 2,500—was the first attempt at a nationwide tally. Meanwhile, British Colombia and Alberta, two of Canada’s most populous provinces, have declared a public health emergency and crisis, respectively, boosting funding for addiction treatment and increasing access to naloxone.

Australia. Heroin use in Australia declined following an abrupt shortage of the drug in 2000, but the country has seen a sharp increase in the use of prescription opioids, now the cause of more than two-thirds of opioid-related deaths there. In 2012, the health ministry announced it would launch a nationwide electronic system already being used in Tasmania to monitor opioid prescriptions, but it has not yet been rolled out. The government is expected to ban over-the-counter painkillers containing codeine starting in 2018, noting that the move is a “very broad-brush approach” to the issue.